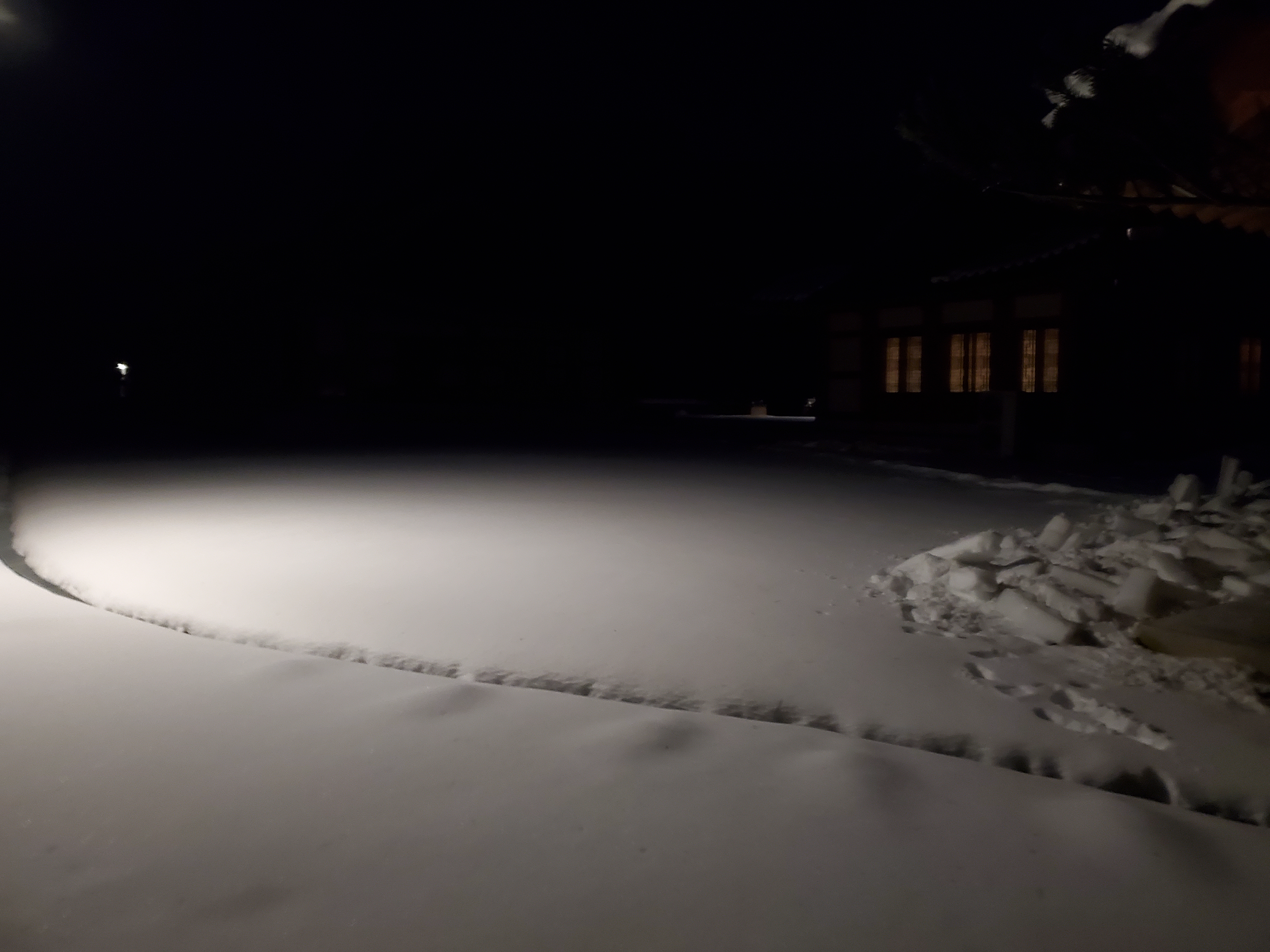

Winter in Odaesan National Park looks like lanky Aspen trees with an inviting snow footpath. Persimmons hang to dry for people to enjoy a sweet bite of their sticky flesh. Crows meet in the middle of a snow field, and a river doesn’t know whether to flow or freeze. The worship halls become lanterns in an inhospitably cold forest night. These were my daily scenes for an 8-day meditation program hosted by Woljeongsa Temple and a U.S. based Buddhist organization, which I was fortunate to discover on a forum.

Whether through spiritual or natural retreat, it’s important to take sanctuary from the social and conditioned congestion in our lives.

During that unassuming week in January, conversations about Global Buddhism unfolded. The Abbot of Woljeongsa Temple, a tall man with impressive eyebrows, and Venerable Y., an energized Taiwanese nun and scholar, met with our program members to talk about the temple’s role in future International Buddhist dialogues, as well as host to one such program in July 2024.

The idea of Buddhist traditions coming together to form a Global Buddhism is interesting: Theravada, Mahayana of East Asia, and now Western Buddhism. Venerable Y. speaks at great length about her vision to connect different schools of thought. While Western Buddhism is still in its infancy, Eastern Buddhism is grounded in the historical and cultural lineage of East Asia, which is why it’s important to bring people to learn in this setting.

In Korea, the main Buddhist sect of the Jogye Order has its emphasis in Seon (known as Chan in China and Zen in Japan). Venerable Y. and Monk W. elaborated on the profound connection between the Odaesans of China and Korea, highlighting Woljeongsa’s revered status as one of the three holiest temples in Korea. This is in part due to its possession of Buddha’s head bone — a sacred relic gifted from Manjusri Bodhisattva to Jajang Yulsa of the Silla Dynasty, who went to study in China.

In addition to its legacy in Korean Buddhism, Woljeongsa is well situated on a logistical level. The nearby venues from the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics enables the region to accommodate large conferences, while the renowned Gangneung Beaches serve as an additional regional attraction. As we finished our tea, the discussion ended with electric chatter around the future of Buddhism, AI, and Woljeongsa’s potential role in Global Buddhism.

The next morning in the -16c walk to chant, I wondered what this might look like. Religion and modernity are increasingly at odds today, yet the humanistic aspect of spiritual practice is more urgent than ever.

My eyes gleaned on the moon. Where might the Buddha head bone be?

Today we might use the terms “mindfulness”, “meditation”, and “present” interchangeably, but there is a lot of overuse and watering down of these concepts through popular culture and self declared experts. It is one of the reasons I like to engage in meditation through a religious setting, where there is a long standing tradition both scholastic and practical.

For the first few days of our meditation program we stayed at the Odaesan Meditation Village (OMV), which is a small compound right at the entrance of the park, and a short beautiful walk from the main temple through the Woljeongsa Fir Forest Trail.

To summarize in brief, we had meditation at the OMV conference hall which was as follows: (25 minutes of sitting meditation + 5 minutes of walking meditation) x 4 = 2 hours. We did this in the morning. In the evening we followed this set up x 2 + a 30 minute Dharma talk.

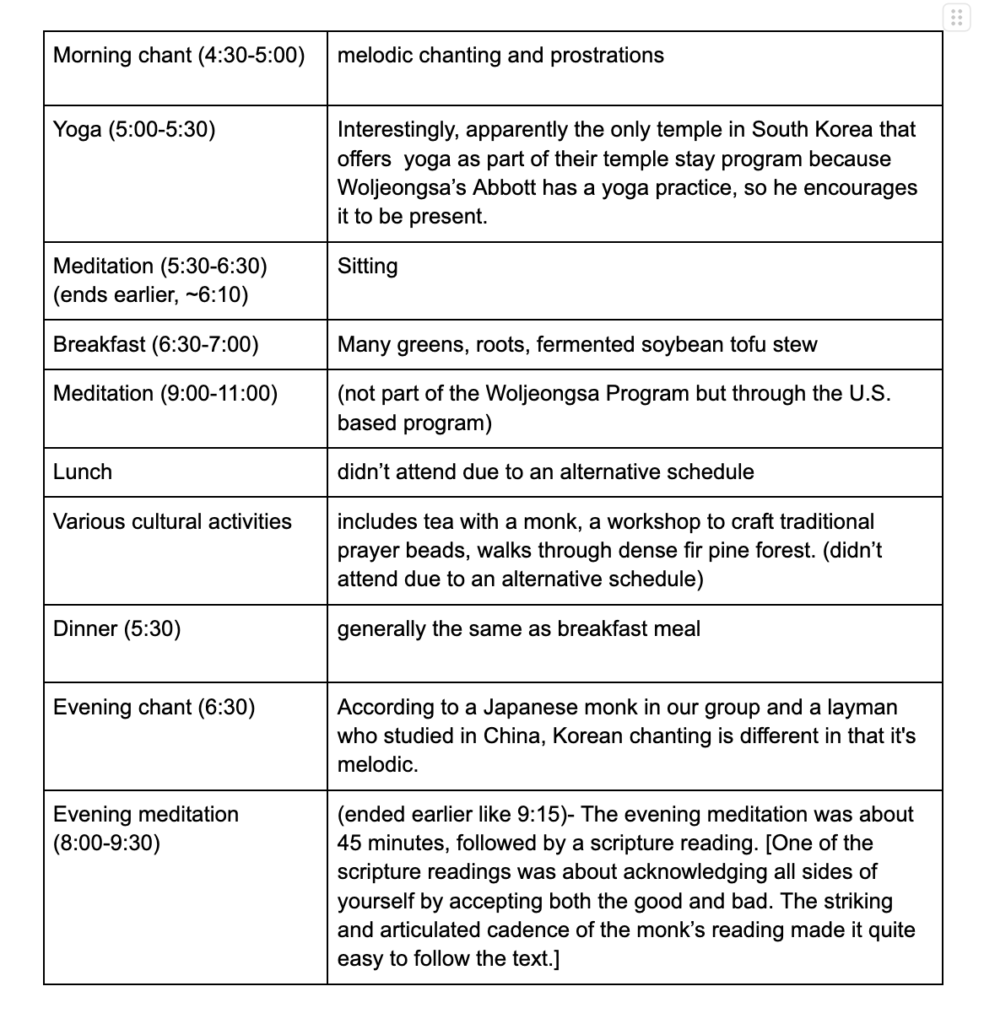

Afterwards, we spent a few days at the Woljeongsa Temple Stay Program. It was a great experience and similar to the other Temple Stay programs I attended, with the exception of yoga and some cultural activities. There, our schedule was as follows:

It’s interesting that several of our program members commented on the chanting differences in Korea versus other Asian traditions. Even at the Bhikkhuni (Nun) Association in Seoul, a nun chanting sutra prompted an observational remark from Venerable Y. In Taiwan, where she was ordained, it is tradition to have several nuns chanting. It would be worthwhile to explore the regional and cultural nuances in Buddhism and learn about sound and auditory role in somatic spiritual experiences.

While I entertained possible research areas, one question remained consistent. With the interactions between Woljeongsa and the U.S. buddhist program representatives, I was curious about the bureaucracy of religion and the role of Buddhism in today’s society.

During our second evening Dharma talk, there were questions about how Buddhism in Korea has transformed. For example, there used to be sangha (community) ties between the villagers and monks through almsgiving of food, or a temple would grow its own sustenance. The Theravada tradition in South East Asia still practices food almsgiving while in Korea, Buddhist temples have adapted to contemporary society through use of monetary transactions. However, by caring for the spiritual needs of its community and addressing people’s concerns in society, Buddhism’s role in Korea has remained the same.

An example of this is through Dharma talks, which allows lay people to ask questions about Buddhism or present concerns in their life.

One participant asked: “How do I balance my ambitions in the workplace with the suffering it causes?”

Our Dharma talk nun replied: “If it causes continuous suffering, it isn’t your purpose. If it really is your true purpose then it won’t cause continuous suffering.”

This sentiment, while seemingly familiar, was new to me. In my own education and upbringing I was taught that suffering sows reward. But it makes sense to differentiate between continuous and temporary suffering, much like one would with pain due to illness or pain due to growth.

Another layman asked about increasing depression among youth in Korea, and how it can be solved as a society. Other participants echoed their concerns about critical social issues.

In the subsequent days, I thought about collectivism in Korea, its benefits and drawbacks. When I returned to Seoul and internet access, I found this essay from a Buddhist forum that describes the difference between healthy community and unhealthy collective ego:

Ego also goes beyond the individual. In fact, its most damaging form may be collective ego, the larger selves many people identify with. My race, my country, my party, my religion, my gender, my class, etc. The eight worldly concerns go from good or bad for me to good or bad for us, but it’s all the same thing. These collective egos are different from the genuine feelings of connection and solidarity that sustain many communities, which have more of the quality of nonego. They are about a bigger, better, more powerful me. They create classes of “others” and are often vehicles of domination.

Racism, sexism, nationalism, colonialism, authoritarianism, militarism, fundamentalist religion, and in some ways capitalism all draw their strength from the seductive power of collective ego—its energy, empowerment, self-righteousness, sense of purpose and community, and the concrete rewards it offers. I think we can fairly say that collective ego is and always has been the most destructive force in human society…

https://www.lionsroar.com/no-self-no-suffering/

The blurred line between community and collective ego in Korean society plays a large role in its nationalism and capitalism, manifesting in its social issues. What does a sustainable “nonego” community look like? And how can Korean Buddhism help shape this?

After the Dharma talk we said our goodnights and everyone returned to their lodgings across the bridge. I stayed behind to sit alone in the still winter night. When else would I have this time?

The beauty of Korea’s mountains and forests are only more captivating as the seasons change. While I had visited Woljeongsa last fall in a backdrop of luminous crimson reds, canary yellows, and bright orange leaves, in the white and icy landscape, it was a different place.

As a site, Woljeongsa has an abundance of architectural and cultural assets. After gaining official temple status in 1377, it experienced numerous fire damages and reconstructions due to war. Yet it has remained to this day, a complex made up of more than 60 temples, 22 pagodas, eight monasteries, and four National Treasures that are nestled throughout the mountains. During our stay, icy roads made it impossible to visit areas other than the main site, but we were fortunate enough to see two National Treasures. The first, the famous Woljeongsa Octagonal Nine Storey Stone Pagoda of the 10th century, is a 15.2 meters stone pagoda representative of the Goryo Period style and National Treasure number 48. The second, the bronze bell of Sangwonsa, is the oldest temple bell produced in Korea and National Treasure number 36.

In Korean history, Buddhism played a state role as the official religion until the Joseon Dynasty, when it was replaced by Confucianism and subsequently suppressed. While it has changed in some ways, it continues to engage in its historical and cultural legacy. To learn more, one can visit Woljeongsa Museum and National Museum of the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, which have extensive historical and archival materials.

While serving domestic needs, Woljeongsa also connects with the International community through dialogues with other Buddhist schools, producing additional support in multicultural understanding. I’m very curious to see what the future of Buddhism will look like, Buddhisms evolving role in addressing social issues, and Korea’s contributions to Global Buddhism.

Reflecting on this transformative 8-day journey during which I uncovered personal and universal layers of questions and connections, I will continue to draw upon the intimate and insightful experiences to guide me. I will remember the conversation with my program members about our inner lives and spiritual practices, the meeting of past and present, west and east.

On days I feel ungrateful, I will remember the delight of a Venerable when drinking ssanghwa-cha (쌍화차), a deep brown and a slightly bitter Korean medicinal tea with dried jujube and pine nuts. A monk’s unbridled laughter and spontaneous English. On days I feel discouraged, I will recall the story of an Abbot who protected Sangwonsa Temple from burning down by confronting soldiers, telling them that if their job is to destroy, his job is to protect. So he will stay in the temple and burn with it. On days I feel overwhelmed, I’ll recall the still snow landscape when the sunbeams sing a soundless warmth and the tall fir and aspen trees overlook the chattery water.

It is my hope that everyone can find time to experience a temple stay program or weekend of solitude to themselves. Whether through spiritual or natural retreat, it’s important to take sanctuary from the social and conditioned congestion in our lives.

Resources:

Interested in Temple Stay? Find out more here:

https://eng.templestay.com/temple_info.asp?t_id=woljeongsa